Deconstructing Orientalism: Anti-Arab Racism as a Global Development and Health Problem

by Sam Jarada

Introduction

Anti-Arab racism is an overlooked and normalised type of discrimination. But what drives it? I argue that it’s Orientalism, as noted by Edward Said, which is the way Western societies (the West or Occident) perceive Eastern societies (The East or Orient), particularly those in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA); this occurs through specific ideas, stereotypes, and depictions of the East from the West’s perspective (1, 2). More specifically, he defines Orientalism in three connected perspectives, one of which is: ‘Orientalism is a Western method of dominating, restructuring, and having authority over the Orient’ (1, 2). Unfortunately, Orientalism has negative impacts on Arab populations in MENA and worldwide, notably anti-Arab racism and the dehumanisation of Arabs and, by extension, Muslims, due to Orientalism having colonial roots (1, 2). These narratives not only exist in popular culture and the media, but they also shape how development and global health stakeholders comprehend Arab societies and choose whose health is prioritised. Therefore, to tackle modern health inequities in MENA, addressing Orientalism and how it links to anti-Arab racism and the dehumanisation of Arabs is vital.

Orientalism's Influence on Perceptions and Health

If Orientalism continues to be seen as an abstract theory, its daily consequences are neglected. This is because the stories told about Arabs, in media and policy, gradually solidify into ‘common sense’ ideas about them. As a result of Orientalism being an influential lens in the West, the media portrayals of Arabs have been primarily negative. For example, a book called ‘Reel Bad Arabs: How Hollywood Vilifies a People’ by Jack Shaheen and the subsequent documentary of the same name both alluded to how out of 1,000 films, 936 of them portrayed Arabs negatively (93.6%), compared to 12 positive portrayals (1.2%) and 52 neutral portrayals (5.2%) (3, 4). Some of the commonly used words to describe Arabs in these films include ‘backwards’, ‘savage’, ‘primitive’ and ‘oppressive’, among other negative and reductive connotations and stereotypes (5). In turn, these consistent narratives seep into humanitarian and development practice, influencing which crises are treated as ‘emergent’, which Arab populations are perceived as ‘threatening’ or ’vulnerable’, and what types of health interventions are seen as fundable or legitimate.

Although not all Arabs are Muslims, Orientalism is still pervasive because of how the Western media and political discourse have repeatedly ‘othered’ and demonised Muslims and Arabs, particularly after 9/11, which has fuelled Islamophobia and anti-Arab racism by recreating tropes of violence, danger and backwardness (6), as a way to contrast the superiority of Western societies. Even before that, Orientalism was prevalent not only in the media but also in policy, as seen in the decision-making of Henry Kissinger during the 1973 Arab-Israeli War (7), and in literature, notably in David Lean's film Lawrence of Arabia, based on T.E Lawrence’s experience in the Middle East during World War I (8). Hence, the views of Arabs have been distorted through policy and literature, which helps explain their dehumanisation today. Their suffering and pain during atrocities, like war and genocide, are viewed as normal or deserving in the eyes of Western society.

Furthermore, it is clear how what I discussed so far contributes to dehumanisation and anti-Arab racism. A 2022 paper noted that 80% of news coverage about Muslims between 2018 and 2020 in top Western media outlets portrayed them in contexts related to violence, conflict, or extremism, compared to only 20% portrayed neutral or positive contexts (9). Also, survey data collected from numerous Western countries found that 45-60% of the public link the terms “violent” or “dangerous” with “Muslim” or “Arab” (9), illustrating how internalised negative stereotypes of them were exacerbated by media coverage. Therefore, this data highlights the strong associations between negative media portrayals, Orientalist depictions, and the dehumanising public perceptions that accelerate anti-Arab racism. Another major consequence of these narratives is that they overlook the rich history of the Middle East and North Africa (10), through its diversity and roots of knowledge that we use globally, from mathematics to medicine.

The health impact of Orientalist stereotypes and anti-Arab racism is expansive, which creates healthcare access inequities. One study found that members of Arab communities, including Arab Americans, report decreased rates of healthcare utilisation, primarily due to experiences or fears of discrimination by healthcare providers (11). Despite these outcomes, the self rated mental health of the study participants has been largely positive (Figure 1); this can be attributed to various factors, including family and community support, as well as their practice of healthier eating habits and regular exercise (11). Additionally, one systematic review mentioning the Gulf Cooperation Council noted implicit bias in medical environments, moulded by negative media portrayals, thereby increasing hurdles to healthcare for Arab patients, making it less likely for them to obtain swift and culturally appropriate treatments for physical and mental health conditions (12).

Figure 1: Bar chart of Self Rated Mental Health by the number of study participants (11).

Also, mental health stigma in Arab communities further intensifies the burden. Returning to the systematic review of the Gulf Cooperation Council states, the authors found reduced mental health literacy and the use of inappropriate mental health interventions. Hence, Arab individuals are unlikely to get help or reveal struggles, leading to worse health outcomes (12). To highlight this data further, a multinational population-based study involving 10,036 individuals from 16 Arab Countries found that more than 60% of respondents believed mental illness must be kept secret within families, contributing to greater stigma and refusal to obtain professional help (13). This was similarly found among the Al-Ahsa population in Saudi Arabia, whereby the average stigma scores were high (99.24 ± 15.62), with higher stigma seen in older adults and those with deficient mental health service access (14). As a whole, these same narratives follow Arabs into health systems; when they are framed negatively, they are less likely to be seen as deserving of trust, care or investment. Healthcare workers may unconsciously hold these ideas, while policymakers may emphasise less importance to addressing problems with access, quality, or outcomes among Arab communities.

Personal Health Experiences due to Orientalism

Before looking more at personal health anecdotes and testimonials due to Orientalism, I want to briefly discuss my experience as an Arab Muslim in this context. While growing up in the UK, Orientalism had a profound impact on my identity, as I felt compelled to conceal important values or aspects of myself due to the primary and secondary schools I attended and the people I interacted with more broadly. As I grew older and attended university, where I met people similar to and different from myself, it became easier to express my values and myself much more. In turn, my health and well-being improved significantly, leading me to write about and pursue a career in public health, where I can use what I learnt from my experiences to empower others. Although my initial negative experiences eventually gave way to more positive ones, for other people, it is likely the opposite.

Nonetheless, it is vital not to view these attitudes towards mental and physical health as a natural part of “Arab culture”. They have occurred through specific periods of displacement, authoritarianism, colonisation, war, genocide, and racism, among other atrocities. From the outside, global health and development stakeholders can misinterpret this distrust as a lack of awareness or ‘cultural resistance’, rather than as a rational reaction to decades of violence, surveillance, and broken promises, viewpoints that are rooted in Orientalist frameworks of Arab communities. When communities are consistently punished, monitored, or pathologised by certain institutions, it is understandable that obtaining mental healthcare could be risky or shameful. During the COVID-19 pandemic, one study involving Middle Eastern or Arab American immigrants discovered mental health challenges, fears, and barriers to healthcare access among them (15). One female participant said, “I had a trauma from the whole world, and I had problems every day, fatigue at home, fatigue, not physical but psychological . . . My psyche suffered a lot, I got depressed and I don’t feel the taste of the world anymore . . . I felt internal destruction and I had depression” (15). This statement, among others, showcases how lived experiences of discrimination and social isolation shape well-being among Arab immigrants.

Similarly, in another study involving displaced Middle Eastern adolescents, participants shared anecdotes of social exclusion, stress due to adjusting to new cultural environments, and their need for culturally-tailored support to counteract the negative impacts of hostility and misrepresentation experienced in schools and healthcare settings (16). In another study relating to caregiving, Arab and Arab American families gave testimonials on the pressures to hide the impact of stigma, illness, and spiritual beliefs impacting health decisions (17). Simultaneously, Arab communities have developed impactful support networks, which include their faith-based spaces, community leaders, family, and novel grassroots mental health approaches, in the MENA region and the diaspora. Any effort to enhance mental health must build on these types of care, rather than dismissing them as ‘irrelevant’ or ‘backward’.

Therefore, Orientalism has direct consequences on resilience and mental health outcomes among Middle Eastern adolescents and moulds cultural expectations and experiences, leading to adverse healthcare access and choices. Broadly speaking, these insights cumulatively show anecdotal and qualitative evidence, demonstrating how Orientalist attitudes and anti-Arab racism not only mould public perception but also significantly impact the health, well-being, and healthcare access of people in Arab communities. Hence, moving beyond Orientalism as a frame of reference for Arabs is essential. Below, I present several approaches that can lead to fairer and more equal healthcare access, while also supporting the well-being of Arab populations worldwide.

Call to Action

On an individual level, author Jameel Alghaberi noted that Arab Americans should proactively define their identities through their stories by creating authentic cultural narratives and incorporating multifaceted viewpoints to counter negative depictions and stereotypes perpetuated by the media and mainstream public opinions, rather than relying solely on external validation or constantly correcting misrepresentations (18). Aside from this, he argues for the importance of fostering novel, positive intercultural dialogue and cultural forms through various means, including literature (18). Although he speaks from an American perspective, his points are applicable to Arabs worldwide.

Furthermore, alternative approaches exist for preventing cultural imperialism (an embodiment of Orientalism), which involve integrating participatory policymaking, community perspectives, and human rights into local governance and global health ethics (19). This builds moral and political legitimacy in public health approaches and empowers communities in the MENA region and the Arab world by enabling them to exercise their autonomy. This is preferable to the Western colonialist practices that directly governed them, as was the case after World War I, and now, having leaders who do not always serve their interests. Likewise, in an interview with Alexandre White, he advocates for diversifying expertise and authorship, as well as policies with historical context, and opposes the ‘civilising missions’ in medicine (20).

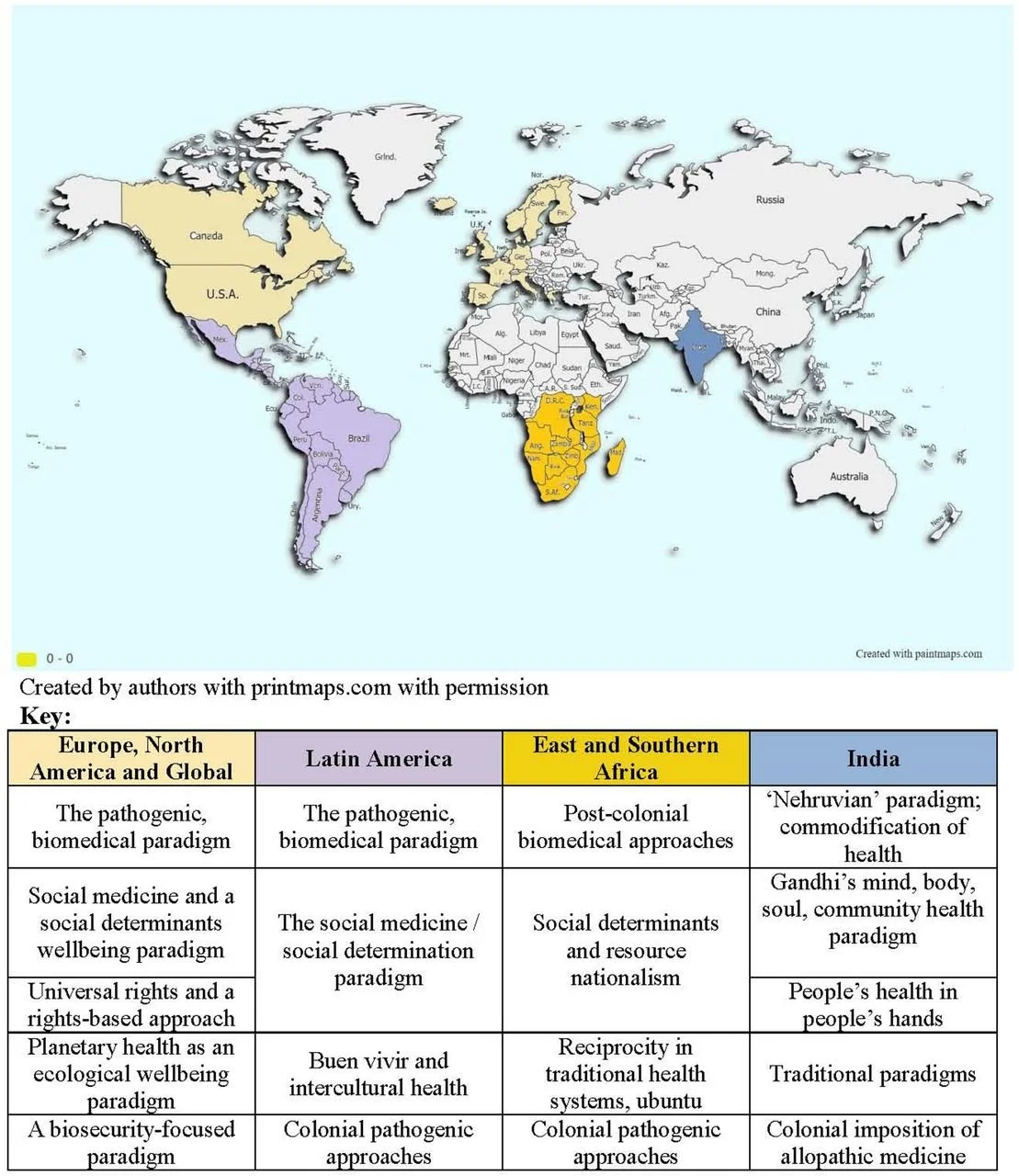

Lastly, one paper on the coloniality of global public health criticised the persistent consequences of ‘bourgeois empiricist’ models (21). It highlighted that public health policymakers and professionals must prioritise deconstructing unfair and unequal social dynamics, as well as prevent academic gatekeeping to reduce health inequities exacerbated by Orientalist thinking and frameworks (21). In a 2021 comparative analysis, the authors emphasised the need to revive broader sociocultural models undermined during the colonial and postcolonial periods (22); they also highlighted the importance of collaboration in protecting renewable and natural resources, as well as encouraging reciprocal education of paradigms between global regions (Figure 2). Hence, undertaking these steps would move away from Orientalist paradigms toward equitable health systems in the MENA region.

Figure 2: Overview of the geographic regions and general paradigms covered amongst them (22).

Conclusion

With everything I covered in this article, Orientalism has significantly contributed to anti-Arab racism and the dehumanisation of Arabs. This is because Orientalism has led to adverse health outcomes, ranging from different people in Arab communities worldwide unable to access essential healthcare services, to the stigmatisation of mental health and the fear of discrimination in Western societies. These inequities reflect a dangerous double standard: while numerous communities are increasingly able to claim their rights, Arabs are still consistently discriminated against and dehumanised through an Orientalist framework that strips them of the same recognition. We cannot allow anti-Arab racism and dehumanisation to be normalised because it will eventually lead to other forms of discrimination being normalised too. For people working in humanitarian aid, global health, and development, this means questioning how their funding decisions, programmes, and narratives might be reproducing Orientalist frameworks rather than deconstructing them. Therefore, dismantling Orientalism is necessary to enhance public health and promote justice globally.

References

Said, E. (1978). Orientalism.

Elmenfi, F. (2022). Reorienting Edward Said’s Orientalism: Multiple Perspective. International Journal of English Language Studies. https://doi.org/10.32996/ijels

Shaheen, J. G. (2003). Reel bad Arabs : how Hollywood vilifies a people.

Jerbi, S., & Szabo, E. E. (2023). FROM VILIFICATION TO CELEBRATION: ARAB AMERICAN COMEDIANS AND THEIR ALTERNATIVE REPRESENTATIONS OF ARABS AND MUSLIMS IN HOLLYWOOD. https://doi.org/10.56734/ijahss.v4n8a4

Taha, M. H. (2014). Gratifying the “Self” by Demonizing the “Other.” SAGE Open, 4(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244014533707

Benzehaf, B. (2017). Covering Islam in Western Media: From Islamic to Islamophobic Discourses. Journal of English Language Teaching and Linguistics, 2(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.21462/JELTL.V2I1.33

YANARIŞIK, O., & AKCA, S. İ. (2022). ORIENTALISM IN HENRY KISSINGER’S FOREIGN POLICY DISCOURSE DURING THE 1973 ARAB-ISRAELI WAR. Anadolu Üniversitesi İktisadi ve İdari Bilimler Fakültesi Dergisi, 23(4), 386–403. https://doi.org/10.53443/ANADOLUIBFD.1134264

Almijbilee Baghdad, S. (2013). David Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia. https://doi.org/10.7176/JEP

Sufi, M. K., & Yasmin, M. (2022). Racialization of public discourse: portrayal of Islam and Muslims. Heliyon, 8(12), e12211. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.HELIYON.2022.E12211

Gao, Z. (2023). A Historical Context, Literary Analysis and Modern Relevance of Orientalism. International Journal of Humanities Social Sciences and Education (IJHSSE), 10, 37–53. https://doi.org/10.20431/2349-0381.1012004

Glass, D. J., al-Tameemi, Z., & Farquhar, S. (2023). Advancing an individual-community health nexus: Survey, visual, and narrative meanings of mental and physical health for Arab emerging adults. SSM. Mental Health, 4, 100281. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SSMMH.2023.100281

Elyamani, R., Naja, S., Al-Dahshan, A., Hamoud, H., Bougmiza, M. I., & Alkubaisi, N. (2021). Mental health literacy in Arab states of the Gulf Cooperation Council: A systematic review. PLoS ONE, 16(1), e0245156. https://doi.org/10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0245156

Stambouli, M., Romdhane, F. F., Jaoua, A., Boukadida, Y., Ellini, S., & Cheour, M. (2023). Cross-cultural comparison of causal attributions and help-seeking recommendations for mental illness : A Multinational Population-Based Study from 16 Arab Countries and 10,036 Individuals. European Psychiatry, 66(Suppl 1), S342. https://doi.org/10.1192/J.EURPSY.2023.746

Alamer, M., Alsaad, A., Al-Ghareeb, M., Almomatten, A., Alaethan, M., & Alameer, M. A. (2021). Mental Stigma Among Al-Ahsa Population in Saudi Arabia. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.19710

Sayed, L., Alanazi, M., & Ajrouch, K. J. (2023). Self-Reported Cognitive Aging and Well-Being among Older Middle Eastern/Arab American Immigrants during the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(11), 5918. https://doi.org/10.3390/IJERPH20115918/S1

Seff, I., Stark, L., Ali, A., Sarraf, D., Hassan, W., & Allaf, C. (2024). Supporting social emotional learning and wellbeing of displaced adolescents from the middle east: a pilot evaluation of the ‘forward with peers’ intervention. BMC Psychiatry, 24(1), 176. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12888-024-05544-2

Leon, C. M. de, & Leon, C. M. de. (2024). AGING, HEALTH, AND CAREGIVING IN ARAB AND ARAB IMMIGRANT POPULATIONS. Innovation in Aging, 8(Suppl 1), 49. https://doi.org/10.1093/GERONI/IGAE098.0151

Alghaberi, J. (2020). Identity and Representational Dilemmas: Attempts to De-Orientalize the Arab. In Postcolonial Interventions (Issue 1).

Muyskens, K. (2021). Avoiding Cultural Imperialism in the Human Right to Health. Asian Bioethics Review, 14(1), 87. https://doi.org/10.1007/S41649-021-00190-2

White, A., & Ribeiro de Sá, G. S. (2025). Toward a historical sociology of infectious disease governance: an interview with Alexandre White. História, Ciências, Saúde - Manguinhos, 32, e2025010. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0104-59702025000100010

Richardson, E. T. (2019). On the Coloniality of Global Public Health. Medicine Anthropology Theory, 6(4), 101. https://doi.org/10.17157/MAT.6.4.761

Loewenson, R., Villar, E., Baru, R., & Marten, R. (2021). Engaging globally with how to achieve healthy societies: insights from India, Latin America and East and Southern Africa. BMJ Global Health, 6(4), e005257. https://doi.org/10.1136/BMJGH-2021-005257