Climate Change Is a Health Issue: Why the Global South Cannot Wait

by Sam Jarada

Introduction

Climate change has a profound influence on global health. The indicators of climate change include rising sea levels, suboptimal temperatures, extreme weather events (ETEs) like storms, floods, droughts, and wildfires; all of these phenomena influence health outcomes across diverse regions (1) through different, intricate pathways (Figure 1). Therefore, it is important to implement policies that bridge environmental sustainability and public health stability. The Global South or low-middle income countries (LMICs) currently grapple with unique challenges due to economic, social, and environmental problems (1). They tend to experience higher levels of poverty and limited access to education and healthcare. These are compounded with the effects of climate change. To tackle these critical problems, it is vital to develop tailored strategies that understand and address their specific needs. Therefore, it is paramount to focus on how climate change impacts the health of people living in the Global South and take fast action to protect their well-being and prevent further complications.

Figure 1: The primary pathways between health outcomes and climate change (1).

Health Impacts of Climate Change and The Importance of Action

Climate change is a complex phenomenon driven by human activities and natural processes, which contributes to the global burden of disease and early mortality (2). For example, air pollution has been declared as a major environmental human health risk by the World Health Organisation (WHO), which annually kills more than 7 million people, mainly causing cardiac, neurological, and respiratory problems (2); the main pollutant gases involved in causing them are particulate matter (PM), ozone and noxious gases, which are emitted from burning fossil fuels (2). With ozone, its harmful effects led to increased hospital admission rates, uncontrollable asthma attacks, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), and more deaths (2). Meanwhile, fine PM (soot) from natural fires and fossil fuels is especially dangerous due to its microscopic size, so it can infiltrate deeply into the lungs and bloodstream, causing health problems such as lung cancer and heart failure (2).

Then, there are persistent organic pollutants (POPs), which cannot be broken down in the environment, and so they accumulate biologically in the food chain, impacting everyone, including fetuses and embryos (2). Also, POPs are endocrine disruptors, meaning they influence hormonal functions and lead to developmental and reproductive impairments, cancer, and neurological disorders (2). Additionally, non-persistent organic pollutants (non-POPs), which are generally included in everyday products, are connected to preterm birth (2). Lastly, increased exposure to heavy metals, such as mercury, lead, and arsenic, poses a high risk of infectious diseases, physiological stress, and negative pregnancy outcomes like preterm birth and delayed fetal growth (2). Overall, it is clear that climate change via air pollution has negative impacts on human health, though it is the Global South countries which bear the brunt of the consequences.

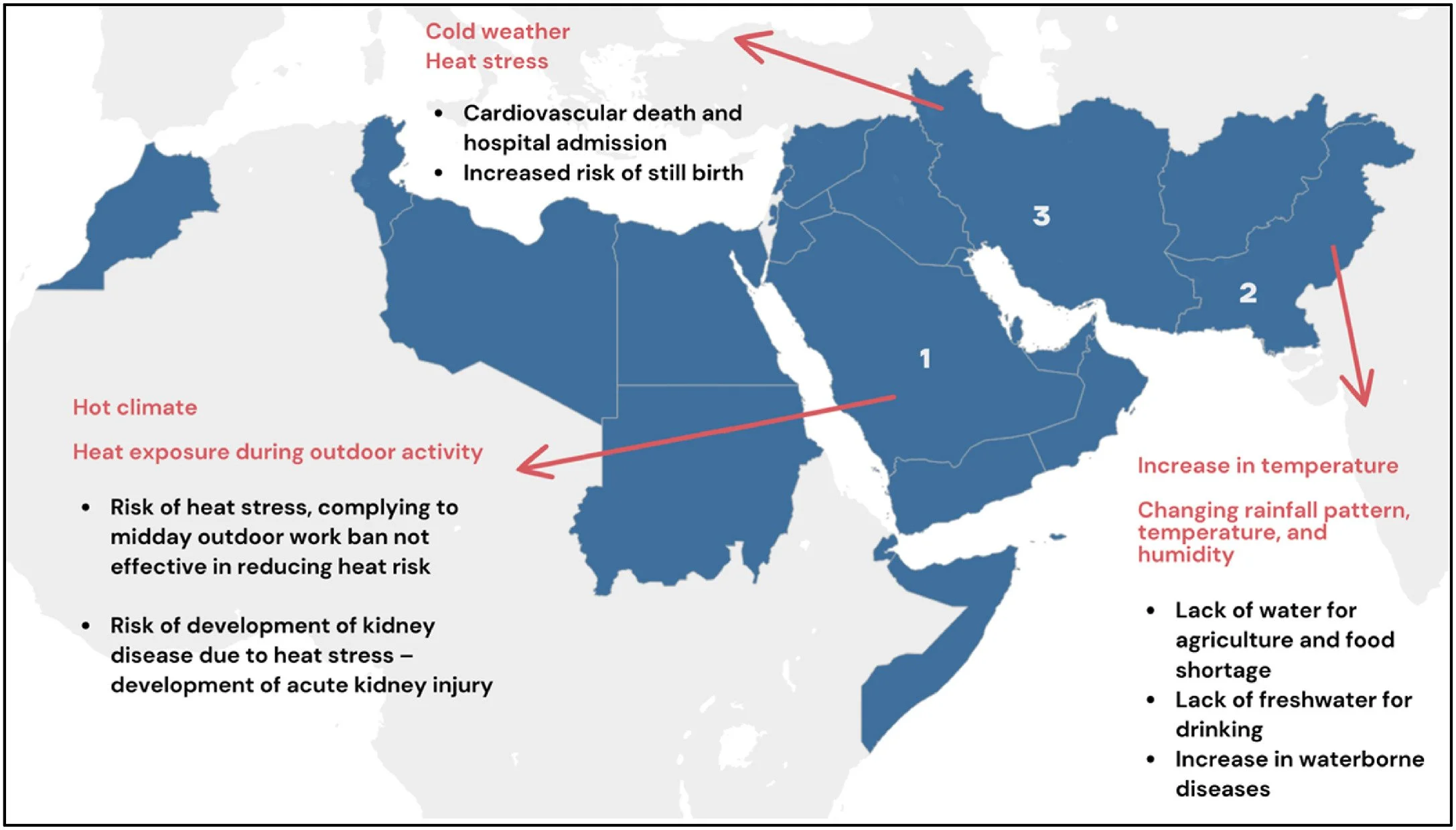

As briefly touched on earlier, the health challenges faced by Global South countries are profoundly entangled with different factors, namely inadequate infrastructure, limited healthcare access, and socioeconomic disparities. With the effects of climate change, their health challenges worsen. For instance, the rising temperatures and changing rainfall patterns exacerbate the incidence of vector-borne infections, such as malaria by forming breeding settings for mosquitoes (3-5), and Dengue by encouraging thermophilic (prefers high temperature) mosquitoes to migrate to countries like Brazil and Singapore (3, 4). Moreover, Flooding affects water sources, leading to higher food- and waterborne diseases like cholera due to contamination (3-5). Additionally, countries like Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, and Iran encounter major health challenges attributable to climate change, ranging from heat stress to waterborne diseases due to a lack of water and contamination (Figure 2). Aside from the impacts on physical health, climate change impairs mental health by directly causing stress and trauma from ETEs, leading to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression and anxiety (1-3, 6), another burden faced by Global South countries.

Figure 2: The health impacts linked to various types of climate change in Saudi Arabia, Pakistan and Iran (2).

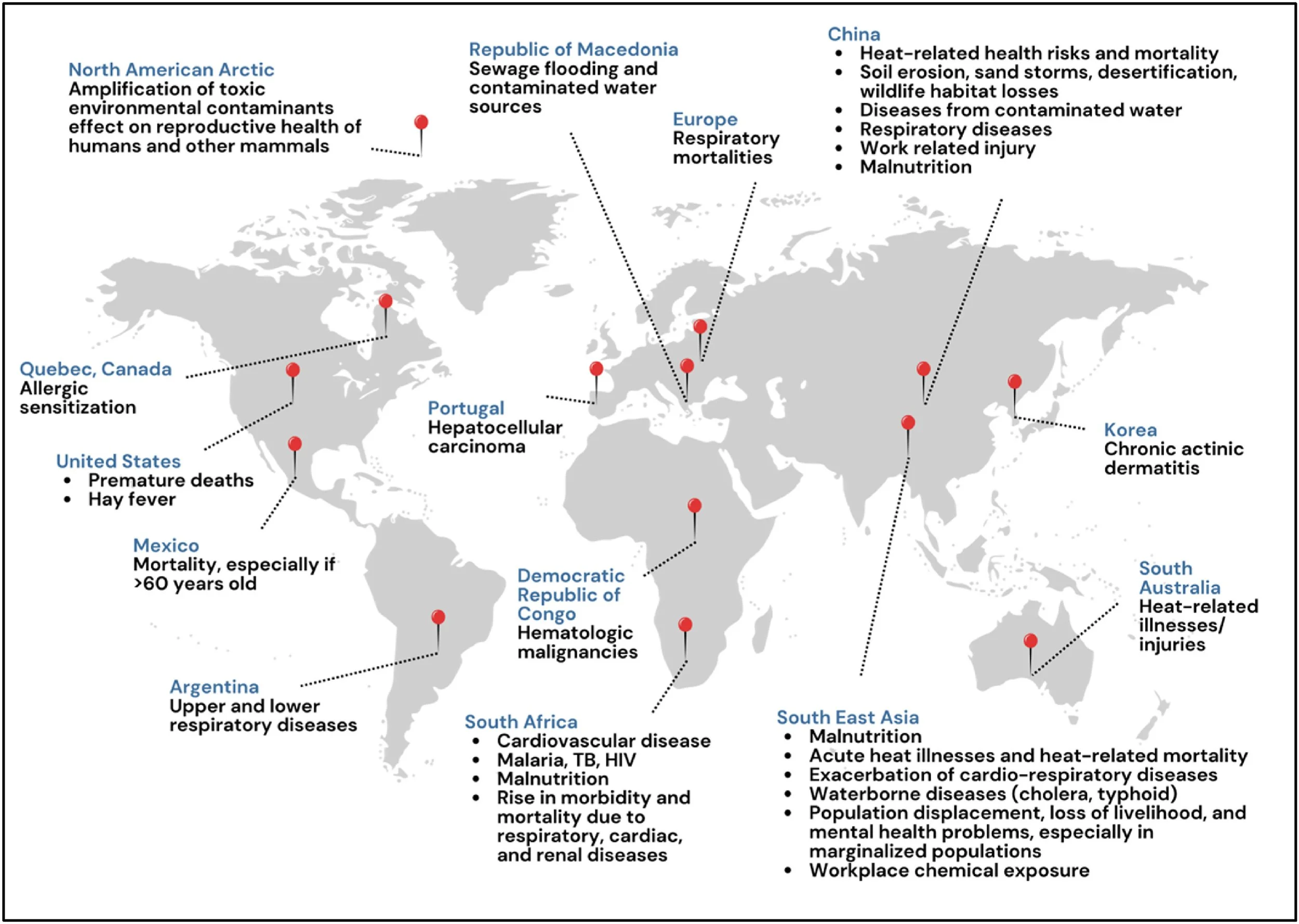

As a whole, climate change is becoming more than only an environmental issue; it is a severe public health challenge impacting countries and regions globally (Figure 3). With the many phenomena of climate change, from rising temperatures to ETEs, the health risks are significant, but as illustrated above, the effects of climate change are complicated and vast (1-6). Moreover, leaving them unaddressed will cause long-term physical and mental health issues as well as negatively impact social and economic structures. Therefore, to effectively tackle these problems, it is vital to continuously understand how climate change and public health are connected through research, among other actions, which will be explored below; one of them includes effective policies to address minimising the impacts of climate change and increasing the resilience of health systems (1).

Figure 3: The health impacts of climate change across various geographic regions and countries (2).

Approaches for Adaptation and Mitigation

To truly tackle the adverse health consequences of climate change, world leaders need to consider these strategies. Firstly, there is building a climate-resilient health system (1, 6, 7), where one scoping review noted several interventions seen to creating these health systems, like enhancing mental health service access and providing sufficient funding (Figure 4). However, there needs to be a more systemic and holistic approach due to its intricate, adaptive qualities (6, 7); this occurs through considering internal health system components and external environmental factors (6, 7). Nonetheless, several challenges that could impede the development of a climate-resilient health system include difficulties in predicting specific health impacts of climate change catastrophes and the existing disparities in how communities are adapting to these impending disasters (8).

Figure 4: The most documented interventions for bolstering a climate-resilient health system (7).

Moreover, there needs to be financial and resource commitment for adaptation and mitigation as the negative impacts of climate change raise health costs and lost lives (7, 9), with studies estimating billions of dollars (9). This should involve approaches such as fortifying early warning systems, elevating public awareness and enhancing healthcare infrastructure (1, 7). On the other hand, two major challenges to overcome are the limitations or variation in technological, social, and financial resources (10), as well as persistent inequities across various countries and regions (8). I believe they could be addressed through multi-sectoral cooperation of environmental, economic, financial, energy, and education sectors, among others, and mandating the integration of health concerns into different policies (7). In turn, this process needs political leadership to address the health risks of climate change in other sectors' programs.

Additionally, the healthcare workforce is critical to recognising, preventing, and managing health risks associated with climate change; this requires integrating it into traditional education, training, and mentoring opportunities through university curricula (7). For example, Harvard Medical School's integrated curriculum aims to prepare future physicians to comprehend and react to the health impacts of climate change (3). Equally, public health responses require improved surveillance, monitoring, infrastructure and education to mitigate threats and prevent diseases and injuries due to climate change (3). Those who would benefit most from these strategies include children, who inhale more air proximate to their body weight and have narrower airways, so they are more vulnerable to climate-induced air pollution (2), and pregnant Women because PM and ozone exposure increases their risk of preeclampsia and premature newborns (2).

For Global South countries, it is vital to ensure that they use solutions tailored to their needs and remedying or preventing adverse health outcomes from rising sea levels, ETEs and other climate change phenomena (1). One way to begin would be to understand the wellbeing and mental health outcomes of climate change mitigation and adaptation approaches in these countries, where one systematic review found that nearly half of the studies documented meaningful beneficial changes (11). In spite of that, the authors acknowledged that the cumulative impact and widespread effectiveness of these approaches were vague due to reporting differences and a lack of qualitative insights (11). To move forward, it is essential to conduct ongoing research into climate change mitigation and adaptation approaches in the Global South, but ensure that there is participation from institutions in these countries to build autonomy and collaboration.

With this said, several Global South countries have implemented effective health interventions to protect, adapt and mitigate against climate change. For instance, China has a National Climate Change Health Adaptation Action Plan (2024–2030), which is a collaborative effort directed by the National Disease Control and Prevention Administration (12). The plan includes step-by-step objectives by 2025, which includes building a policy and standards framework and then by 2030, which includes specifying a complete policy and standard system (12). This plan also outlines 10 important methods for health adaptation, such as enhancing health security capacities and building a supportive societal environment (12). Although not an exact health intervention, this action plan conveys an influential nationwide milestone for China and contributes to global health resilience against climate change, identifying the complicated challenges posed by China's expansive and multifarious population and geography.

International Accountability and Governance

International organisations like the United Nations (UN) and the World Health Organisation (WHO) are essential in tackling climate change and its impacts on health. The WHO academy, for example, was established in 2020 with help from the French Government, and is designed to implement lifelong learning in health globally (13); this platform can support member countries to work concurrently on global health initiatives and climate policies, helping everyone understand how environmental issues affect public health (13). Meanwhile, the UN's Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) specifically underscore the need to ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for everyone, while also fighting climate change and its effects (14). Together, both organisations enable sharing knowledge, resources, and best practices, all to protect the most vulnerable communities and cultivate a healthier, more sustainable future for everyone.

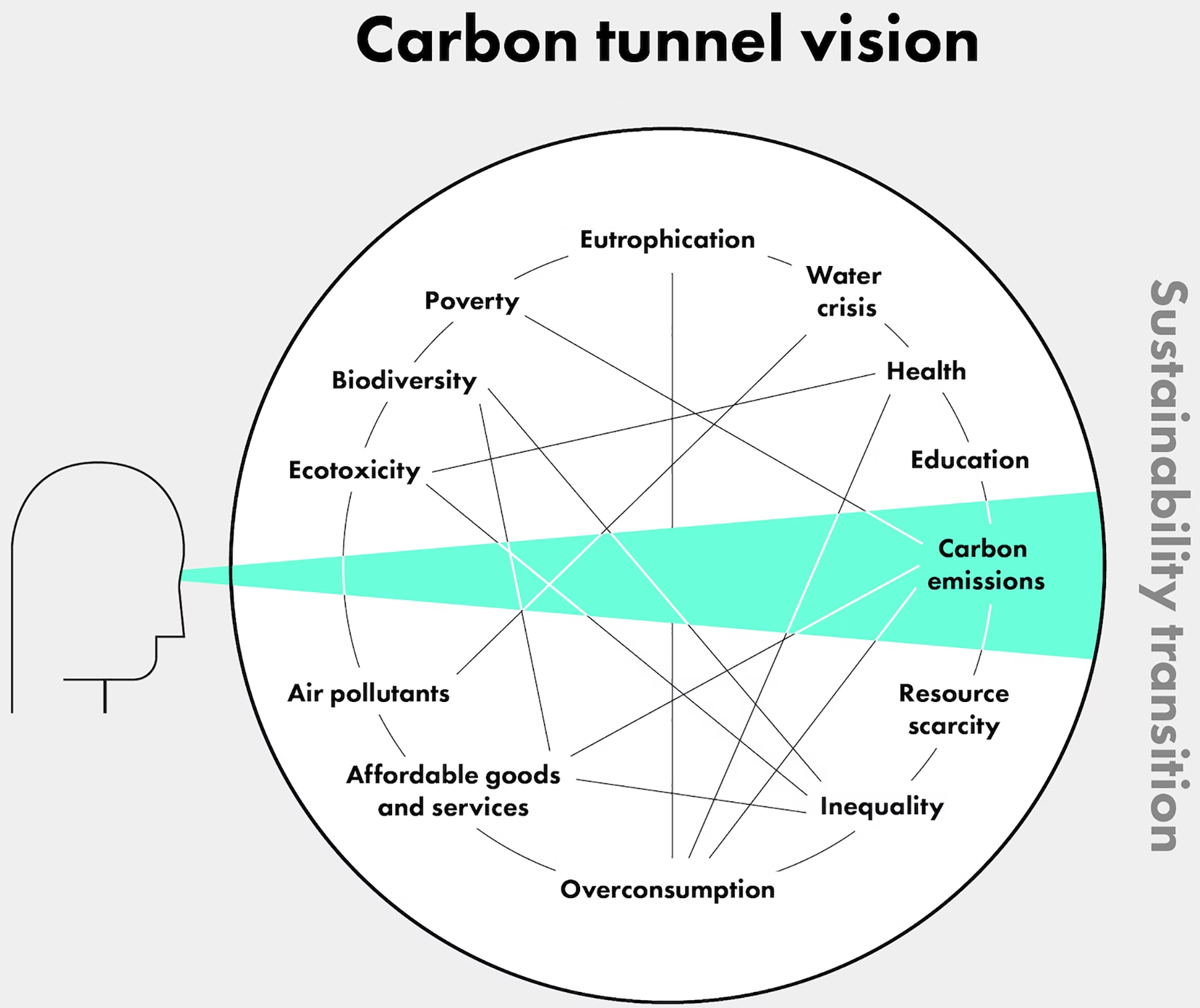

As illustrated above, tackling the health impacts of climate change in Global South countries requires a thorough approach that involves strengthening health systems, raising public awareness and incorporating climate resilience into health policies; this must begin by moving away from the restricted ‘tunnel vision’ of reducing carbon emissions (Figure 5), which overlooks the systemic drivers of environmental destruction and health inequities, thereby obscuring root causes like military activism, trade policies and colonial capitalism (15). Similarly, in humanitarian contexts, acknowledging the impacts of climate change is vital because current humanitarian approaches are already inadequate to meet the existing essentials for vulnerable communities, so any extra hindrance from climate change is challenging (16). Hence, moving forward should involve embedding climate change as a critical problem that is intertwined with others in health, education and policy.

Figure 5: Diagram of ‘carbon tunnel vision’ (15).

The Global North are largely responsible for climate change’s impacts on health through their insufficient laws and regulations to mitigate industrial emissions. However, the WHO European Region did make some progress in the previous decade. Between 2012 and 2017, governance mechanisms had improved with the implementation of health vulnerability and impact assessments, from 77% of responding countries in 2012 to 85% in 2017, which supplies vital data for decision-makers (17). By 2017, 75% of responding countries designed a climate change health adaptation plan with an implementation plan, with 65% having government approval (17). With these systems in place, effectively reducing emissions could stop 138,000 early deaths yearly in the WHO European Region, leading to financial savings between 244 and 564 billion US dollars (17). In turn, this helps the Global South because it fosters sustainable development, economic opportunities and social equity, leading to better living standards and resilience against climate change.

Although there is some optimism about tackling climate change, it is important to re-address the role of industries in driving climate change. As the majority of them operate in Global North countries, their growth came from colonialism and imperialism, which shaped political, socio-economic, and health disparities; this legacy of colonial exploitation continues to control global governments, thereby affecting climate and health policies (18-20). This was similarly noted in a study gathering viewpoints from nurses and their community-based organisations (CBOs) on climate justice; they also mentioned other themes, such as state violence, which is normally enabled by government partnerships with corporations, which allow pollution, ignore community protection, and fail to hold those accountable for ecocide (19). Accordingly, the participants felt governments did not prioritise climate justice. Overall, it is the Global North countries that need to do more to address climate change because it is the Global South who are most impacted on top of their existing problems.

Conclusion

The intricate connection between climate change and health in the Global South highlights how paramount it is to create integrated solutions that put climate policies at the forefront of public health. To tackle the many challenges that overlap with a warming planet, health-focused approaches that tackle the exact vulnerabilities faced by these communities are needed. This should involve elevating the voices of those directly experiencing the impacts of climate change in the Global South. Personal stories and case studies from them can showcase their struggles and resilience. By incorporating these viewpoints into policy discussions, it is possible to devise strategies that are effective, culturally relevant and driven by the community. Furthermore, by building resilience and promoting sustainable practices, protecting the well-being of communities today would even pave the way for a healthier, sustainable future for the generations to follow. Consequently, taking concrete steps is important now to develop policies that foster a world where health and the environment can flourish together. If this is delayed any further, then the Global South will encounter irreversible crises.

References

Zhao Q, Yu P, Rahini Mahendran, Huang W, Gao Y, Yang Z, et al. Global climate change and human health: Pathways and possible solutions. Eco-Environment & Health [Internet]. 2022 May 7 [cited 2025 Sep 22];1(2):53–62. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10702927/

Abdul-Nabi SS, Karaki VA, Khalil A, Zahran TE. Climate Change and Its Environmental and Health Effects from 2015 to 2022: A scoping review. Heliyon [Internet]. 2025 Jan 1 [cited 2025 Sep 22];11(3):e42315–5. Available from: https://www.cell.com/heliyon/fulltext/S2405-8440(25)00695-4?_returnURL=https%3A%2F%2Flinkinghub.elsevier.com%2Fretrieve%2Fpii%2FS2405844025006954%3Fshowall%3Dtrue#fig3

Parums DV. A Review of the Increasing Global Impact of Climate Change on Human Health and Approaches to Medical Preparedness. Medical Science Monitor [Internet]. 2024 Jul 11;30. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC11302257/

Zhang Y. Impact of Climate Change on Transmission Patterns of Infectious Diseases and Public Health Responses. Highlights in Science, Engineering and Technology. 2024 Dec 24;123:71–6.

J Limaheluw, Hall L, Kraker J de, F Serafim, Husman AR. Impacts of long-term climate change on human health: a global scoping review. European Journal of Public Health [Internet]. 2024 Oct 28 [cited 2025 Sep 22];34(Supplement_3). Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11517146/

Yenew C, Bayeh GM, Gebeyehu AA, Enawgaw AS, Asmare ZA, Ejigu AG, et al. Scoping review on assessing climate-sensitive health risks. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2025 Mar 7 [cited 2025 Sep 22];25(1). Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11887272/

Mosadeghrad AM, Isfahani P, Eslambolchi L, Zahmatkesh M, Afshari M. Strategies to strengthen a climate-resilient health system: a scoping review. Globalization and Health [Internet]. 2023 Aug 28 [cited 2025 Sep 22];19(1). Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10463427/

Hess JJ, McDowell JZ, Luber G. Integrating Climate Change Adaptation into Public Health Practice: Using Adaptive Management to Increase Adaptive Capacity and Build Resilience. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2012 Feb;120(2):171–9.

Bikomeye JC, Rublee CS, Kirsten. Positive Externalities of Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation for Human Health: A Review and Conceptual Framework for Public Health Research. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health [Internet]. 2021 Mar 3 [cited 2025 Sep 22];18(5):2481–1. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7967605/

Huang C, Barnett AG, Xu Z, Chu C, Wang X, Turner LR, et al. Managing the Health Effects of Temperature in Response to Climate Change: Challenges Ahead. Environmental Health Perspectives [Internet]. 2013 Feb 13 [cited 2025 Sep 22];121(4):415–9. Available from: https://ehp.niehs.nih.gov/doi/10.1289/ehp.1206025

Flores EC, Brown LJ, Ritsuko Kakuma, Eaton J, Dangour AD. Mental health and wellbeing outcomes of climate change mitigation and adaptation strategies: a systematic review. Environmental Research Letters [Internet]. 2023 Dec 13 [cited 2025 Sep 22];19(1):014056–6. Available from: https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1748-9326/ad153f

Ji JS. China’s health national adaptation plan for climate change: action framework 2024–2030. The Lancet Regional Health - Western Pacific [Internet]. 2024 Oct 22 [cited 2025 Sep 22];52:101227–7. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11532759/

Prats EV, Neville T, Nadeau KC, Diarmid Campbell-Lendrum. WHO Academy education: globally oriented, multicultural approaches to climate change and health. The Lancet Planetary Health [Internet]. 2023 Jan 1 [cited 2025 Sep 22];7(1):e10–1. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9834511/

THE 17 GOALS | Sustainable Development [Internet]. Un.org. United Nations (UN); 2015 [cited 2025 Sep 30]. Available from: https://sdgs.un.org/goals

Deivanayagam TA, Osborne RE. Breaking free from tunnel vision for climate change and health. Pai M, editor. PLOS Global Public Health [Internet]. 2023 Mar 9 [cited 2025 Sep 30];3(3):e0001684. Available from: https://journals.plos.org/globalpublichealth/article?id=10.1371/journal.pgph.0001684

Schwerdtle PN, Irvine E, Brockington S, Devine C, Guevara M, Bowen KJ. “Calibrating to scale: a framework for humanitarian health organizations to anticipate, prevent, prepare for and manage climate-related health risks.” Globalization and Health [Internet]. 2020 Jun 26 [cited 2025 Sep 29];16(1). Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7318416/

Vladimir Kendrovski, Schmoll O. Priorities for protecting health from climate change in the WHO European Region: recent regional activities. Bundesgesundheitsblatt - Gesundheitsforschung - Gesundheitsschutz [Internet]. 2019 Apr 18 [cited 2025 Sep 22];62(5):537–45. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6507478/

Vivek Nenmini Dileep. Climate Change and Global Health Governance in Relation to the Global South and the Global North. Nuovi Autoritarismi e Democrazie Diritto Istituzioni Società (NAD-DIS) [Internet]. 2022 Dec 23 [cited 2025 Sep 30];4(2). Available from: https://riviste.unimi.it/index.php/NAD/article/view/19467

LeClair J, Dudek A, Zahner S. Climate Justice Perspectives and Experiences of Nurses and Their Community Partners. Nursing Inquiry. 2024 Dec 16;32(1).

Viveros-Uehara T. Climate Change and Economic Inequality: Are We Responding to Health Injustices? Health and Human Rights [Internet]. 2023 Dec [cited 2025 Sep 30];25(2):191. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10733765/