Anti-Racism in Humanitarian Health Action: Should We Move Beyond Colonial Models?

by Sam Jarada

1. Introduction

Many countries in the Global South or low-middle income countries (LMICs) rely on humanitarian aid from organisations like Action Against Hunger and UNICEF (United Nations Children's Fund), which continuously support the most vulnerable communities. Unfortunately, most aid they provide is short-term solutions to tackle long-term health crises that vulnerable communities frequently encounter, i.e. chronic or infectious diseases. Also, the aid international or national organisations provide cannot address the deep-rooted social and economic issues that Global South countries experience, such as displacement and hyperinflation. To tackle these problems, humanitarian organisations should adopt more anti-racism and anti-colonial approaches for three reasons. Firstly, it puts the voices of formerly colonised countries at the centre of aid. Secondly, it would ensure that the problems above are addressed for the development of Global South countries. Thirdly, it can lead to an equal and equitable relationship between the Global North and South countries. Otherwise, if they go unaddressed, then these problems would exacerbate.

One example of an anti-racist and anti-colonial approach includes noting marginalised scholars' work and inviting them to publicise in mainstream journals to showcase their work (1). Prioritising them lets humanitarian organisations attain insights from their communities' lived experiences, which enhances interventions, making them suitable and culturally sensitive. However, they need editors to adopt modesty and surrender authority, assuring publication is unrestricted by traditional governance structures (1). Another approach involves questioning partnerships, privileges, and detriments in the colonial framework of power (1). This prompts questions about who conducts research, who is asked to participate, and the reasons behind these options (1), by revealing power imbalances. Finally, funders should be encouraged to invest in projects conducted by researchers from non-dominant backgrounds (1), which entrust communities and ignite creative resolutions to distinct health challenges, promoting ownership and agency in health endeavours.

Overall, this article argues for incorporating anti-racist and anti-colonial approaches in humanitarian health action, concentrating on the voices of Global South communities impacted by systemic inequities and inequalities. Also, it will critique standard methods that perpetuate colonial power dynamics and suggest fairer frameworks to tackle health and social issues. Emphasising these approaches can promote greater agency and ownership within impacted communities and encourage a transformation in humanitarian health.

2. Historical Context and Current Methods

Although colonialism historically existed in various forms, it is European colonialism which had long-lasting impacts on current humanitarian health systems. Global health's history is profoundly interwoven with colonial conquest and ideas of cultural hierarchy and supremacy, which were used to justify authority over 'the other' (2). Colonialism had institutionalised and normalised racism through superiority and differences, leading to financial exploitation and cultural domination (2). Moreover, early global health actions were created in these backgrounds, often conditional on coercive governments and designed to shield European and American personnel, while local medical knowledge was devalued (2). This occurred through epistemic violence, a pervasive global health problem that involves disqualifying knowledge (2), particularly from Global South countries; they were framed as ‘uncivilised’ and ‘illegitimate’ to assert superiority, damaging precolonial systems, despite their contributions to innovation (2). Another form of colonialism influencing humanitarian health systems is settler colonialism, a continuous social construction whereby external populations (notably European) live on and maintain supremacy over Indigenous lands (2, 3).

Unlike franchise colonialism (which is extractive), settler colonialism aims to remove and replace Indigenous populations, collapsing the difference between ‘coloniser’ and ‘colonised’ (2, 3). The impacts of this colonialism type profoundly impact humanitarian health systems. For example, they typically prioritise settlers, which often neglects the needs of Indigenous health and knowledge (4). In turn, Indigenous populations experience healthcare inequalities and inequities, as well as essential services that do not coincide with their cultural practices and traditions (4, 5).

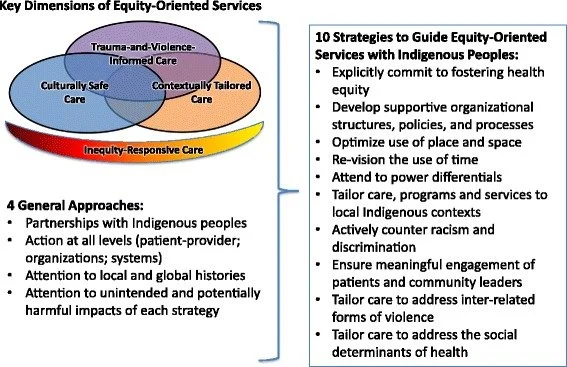

One ethnographic study noted that supporting the healthcare of Indigenous people in Canada should involve approaches, such as culturally safe care and trauma-informed care (TVC) (5), among other strategies (Figure 1), which could be transferred into humanitarian contexts. However, the outcomes of settler colonialism persist through cycles of mistrust and disengagement between healthcare providers and Indigenous populations, further aggravating health disparities (6, 7). This makes administering vital humanitarian aid complicated unless there is a conscious need for these organisations to acknowledge the history of marginalisation encountered by Indigenous populations from settlers.

Figure 1: Important aspects of Equity-Oriented primary healthcare with Indigenous peoples (5).

There have been recent efforts toward tackling racism within health contexts. For example, the Black Lives Matter movement has prompted conversations on practical strategies for change, examining whether decolonisation is feasible within systems built to support colonialism (8). Also, one cross-sectional study reviewed US global health programs, to identify strengths and gaps in anti-racist and anti-colonial education (9). The authors found that programs addressed health inequity, cultural humility, immigrant and refugee health and examined a person’s motivation for engaging in global health (9). However, there was a 44% response rate among those running the programs, so there was not enough accurate representation of all the programs, and the time administering the surveys was during the COVID-19 pandemic, which may contribute to the response rate (9). Moreover, the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai integrated anti-racism into their curricula and institutions, which can provide an evolving standard for continuous transformation (10). I believe this should be extended within humanitarian organisations to ensure the aid they provide coincides with tangible decolonisation efforts through education.

Also, there are multi-component anti-racist endeavours in public health and academic medicine schools, which emphasise community engagement and reform in training, research, and practice for structural shifts (11). In Brazil, they incorporated anti-racism and equity training for staff working in women’s health, which led to tangible improvements in maternal outcomes (12). In New Zealand, authentic healthcare vignettes were used to create practical micro-, meso- and macro-level interventions, which showed teachable moments and effectiveness of anti-racist practices in institutions (13). In humanitarian organisations, I believe these methods can be helpful while providing aid because they can encourage workers to support vulnerable populations through mutual understanding and respect for their culture. Although all of these efforts were implemented to tackle anti-racism and anti-colonialism, they persist in health systems.

3. Defining Anti-Racism during Health Crises

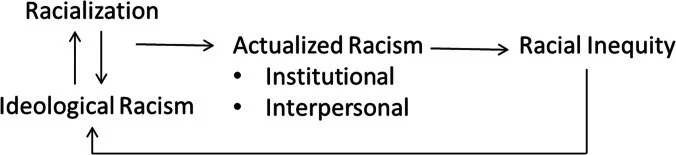

Although societies, to some extent, have become more equal and equitable, there are still significant gaps within systems perpetuated by pre-existing racism and colonialism. One contributor is racialisation, where racial category social structures are often based on features believed to reflect other differences, such as morality or intelligence (14). This is entangled with racial stratification, leading to unequal and inequitable access to resources and power, which is further exacerbated by interpersonal, ideological and institutional racism (Figure 2). In turn, racism negatively affects health psychosocially, whereby internalised racism can damage mental health by declining self-esteem within stigmatised communities (14); continuous exposure to interpersonal racism can initiate chronic stress, impacting mental and physical health. In humanitarian contexts, racism can hinder aid access for affected communities, leading to mistrust in humanitarian organisations and worsening health.

Also, racism affects access to health-promoting resources in the United States. For instance, policies, such as redlining, historically limited where Black families can live, causing neighbourhood segregation, decreasing home values, and homeownership (14). This equally contributed to environmental injustices, through increased air pollution from highways constructed via these neighbourhoods (14). Other policies, like taking land from Native Americans and disproportionately incarcerating ethnic minorities, also led to current racial inequalities and inequities (14). Going back to COVID-19, focusing on how the UK handled it, one paper noted that the disproportionate socioeconomic impact and mortalities in racial and minority communities were inevitable (15). This is because these outcomes were profoundly rooted in social structures, and not only due to the virus's biological characteristics or its hosts (15). Hence, the pandemic revealed and intensified structural health vulnerabilities.

Figure 2: A conceptual model attaching racialisation to racial inequity through actualised and ideological racism (14).

Despite institutionalised racism being a principal determinant of health, one review noted that within the broader literature, it is infrequently and secondarily addressed in peer-reviewed research. The authors advocate for clear labelling and centring institutionalised racism in prospective studies for meaningful progress toward health equality and equity (16). Currently, physicians encounter systemic racism, shifting from the thought that it is apolitical and exclusively science-based (17). Although this occurred, a paradox exists where healthcare professionals, who appear to champion equity and equality, work in systems perpetuating racist policies (17, 18); historical and ongoing research showcase these healthcare policies and practices, but professionals do not always recognise their complicity or that of their organisations (18). For example, treating obesity remains a persistent medical challenge, hindered by racism, whereby ethnic minority patients are less likely to receive obesity diagnoses and treatments (17). Moreover, Western corporate food systems, which are usually unregulated due to 'commercial speech' protections, disproportionately target ethnic minority communities with their unhealthy products, creating obesogenic environments (17).

Lastly, connecting systemic racism and colonialism to how malaria is tackled among global health institutions is essential. In Africa, European colonialism was hindered by malaria due to high mortality rates among White settlers, which compromised business and military interests (19). Hence, controlling malaria was vital to ensure these interests were uncompromised, leading to the development of global health from tropical medicine by former colonial and military officers pursuing prestige and payment during the 20th century (19). The first tropical medicine schools in Liverpool and London were established with aid from the Colonial Office and shipping companies, so there is a clear link between malaria and colonialism (19). Furthermore, malaria prevalence is worsened through practices such as forced labour, migration, and large-scale agriculture, creating new breeding sites for vectors, spreading parasites, and increasing vulnerability due to poverty and poor nutrition (19).

Moreover, the control strategies for malaria, like bednets and pharmaceuticals, are primarily privately-owned commodities, differing from environmental and public health advancements that eradicated malaria in Global North countries (19). Therefore, humanitarian efforts to control and eliminate malaria must shift from the Global North countries towards those in the Global South to minimise its devastating impacts.

4. Recommendations

To move towards equality and equity, several strategies are needed to integrate anti-racism and anti-colonialism in health responses. For example, gradual positive changes in global health publishing through reflexivity statements and inclusive peer review, while helpful, are inadequate to disrupt the underlying approaches and structures of coloniality because significant disparities persist (20). Therefore, pressing and substantial changes are needed to correct epistemic pluralism, foster mutual trust and respect, and promote collaborative action for organic solutions in global humanitarian health responses (20). Another approach is adopting a 'bidirectional decoloniality', which confronts settler colonialism and racial injustice in the Global North as urgently as it addresses colonialisms in the Global South (3). Focusing only on transnational solidarity without considering the local settler colonial contexts can unintentionally reinforce colonial mindsets (3). This bidirectional approach looks to disrupt the exploitative, extractive, and eliminatory mindsets that naturalise hierarchies that perpetuate health inequities between colonised and colonising societies (3). Practical actions include learning local Indigenous histories, ethical research by supporting marginalised scholars, and advocating for reparations as a real solution to achieving health equity and justice (3).

Physicians hold tremendous power within healthcare systems and must confront the structures shaping health (17). This should involve amplifying patients’ and providers’ voices to sustain fundamental changes, including the social determinants of disease into patient care, and developing partnerships across various fields and groups to address the laws and social factors which can contribute to disease (17). Thinking more broadly, all healthcare professionals must actively advocate for policy development to remove institutional racism in healthcare at all governmental levels (18). In turn, humanitarian health interventions are shaped by the lingering consequences of colonialism and racism, creating disparities for communities in the Global South. By adopting anti-racist and anti-colonial strategies, organisations can tackle entrenched social issues more effectively, uplift marginalised voices, and honour Indigenous practices. Sustaining a diverse group of researchers fosters community ownership and sparks innovation, ultimately leading to a more equitable and equal humanitarian health system.

5. Conclusion

Overall, humanitarian organisations must adopt anti-racist and anti-colonial frameworks to tackle long-term health problems in the Global South adequately. One of the most vital approaches they need to consider is combining insights from marginalised scholars, which ensures that interventions are culturally sensitive and embedded in local Indigenous knowledge. Nonetheless, it is equally important to address the enduring impacts of colonialism, which currently shape humanitarian health and perpetuate racism, as well as neglect the needs of Indigenous communities. Prospectively, anti-racist and anti-colonial approaches are needed in humanitarian health systems to uphold equity and equality in healthcare for marginalised communities. By proactively confronting systemic biases and amplifying the voices of historically marginalised communities, developing health interventions to cater to these communities' unique needs and challenges is genuinely possible. This approach not only enhances health equity, but also strengthens the resilience of whole communities, paving the way for effective humanitarian responses and is rooted in justice, honouring various health experiences and outcomes.

6. References

Naidu T. Modern Medicine Is a Colonial Artifact: Introducing Decoloniality to Medical Education Research. Academic Medicine [Internet]. 2021 Aug 12 [cited 2025 Aug 27];96(11S):S9–12. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/academicmedicine/fulltext/2021/11001/modern_medicine_is_a_colonial_artifact_.6.aspx

Zeinabou Niamé Daffé, Guillaume Y, Ivers LC. Anti-Racism and Anti-Colonialism Praxis in Global Health—Reflection and Action for Practitioners in US Academic Medical Centers. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene [Internet]. 2021 Jul 19 [cited 2025 Aug 27];105(3):557–60. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8592354/

Bram Wispelwey, Chidinma Osuagwu, Mills D, Tinashe Goronga, Morse M. Towards a bidirectional decoloniality in academic global health: insights from settler colonialism and racial capitalism. The Lancet Global Health [Internet]. 2023 Aug 15 [cited 2025 Aug 27];11(9):e1469–74. Available from: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/langlo/article/PIIS2214-109X(23)00307-8/fulltext

Barnabe C. Towards attainment of Indigenous health through empowerment: resetting health systems, services and provider approaches. BMJ Global Health [Internet]. 2021 Feb 1 [cited 2025 Sep 4];6(2):e004052–2. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7871239/

Browne AJ, Varcoe C, Lavoie J, Smye V, Wong ST, Krause M, et al. Enhancing health care equity with Indigenous populations: evidence-based strategies from an ethnographic study. BMC Health Services Research [Internet]. 2016 Oct 4 [cited 2025 Sep 4];16(1). Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5050637/

Horrill T, McMillan DE, Schultz ASH, Thompson G. Understanding access to healthcare among Indigenous peoples: A comparative analysis of biomedical and postcolonial perspectives. Nursing Inquiry. 2018 Mar 25;25(3).

Jongbloed K, Hendry J, Smith DB, Kwunuhmen JG. Towards untying colonial knots in Canadian health systems: A net metaphor for settler-colonialism. Healthcare Management Forum [Internet]. 2023 May 17 [cited 2025 Sep 4];36(4):228–34. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10291485/

Hussain M, Sadigh M, Sadigh M, Rastegar A, Sewankambo N. Colonization and decolonization of global health: which way forward? Global Health Action [Internet]. 2023 Mar 20 [cited 2025 Aug 31];16(1). Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10035955/

Fanny SA, Rule A, Crouse HL, Hudspeth JC, Hodge B, Rus M, et al. Anti-racist and anti-colonial content within US global health curricula. PLOS Global Public Health [Internet]. 2025 Feb 6 [cited 2025 Sep 6];5(2):e0003710–0. Available from: https://journals.plos.org/globalpublichealth/article?id=10.1371/journal.pgph.0003710

Asfaw ZK, Barthélemy EJ. Anti-racist Medical Education in the Transformation of Global Health. Tropical Doctor [Internet]. 2022 Feb 1 [cited 2025 Sep 6];52(2):245–5. Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/00494755221077807

Hall JE, Boulware LE. Combating Racism Through Research, Training, Practice, and Public Health Policies. Preventing Chronic Disease [Internet]. 2023 Jun 26 [cited 2025 Sep 6];20. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10317032/11.

Nariño S, Francisca, Brito T, Pedrilio LS, Borem P, Garcia C, et al. Strengthening equity and anti-racism in women’s care: a quality improvement initiative reducing institutional maternal mortality in Brazil. International Journal for Equity in Health [Internet]. 2025 Apr 23 [cited 2025 Sep 6];24(1). Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12016309/

Kidd J, Came H, T. McCreanor. Using vignettes about racism from health practice in Aotearoa to generate anti‐racism interventions. Health & Social Care in the Community [Internet]. 2022 Mar 18 [cited 2025 Sep 6];30(6). Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10078765/

Needham BL, Ali T, Allgood KL, Ro A, Hirschtick JL, Fleischer NL. Institutional Racism and Health: a Framework for Conceptualization, Measurement, and Analysis. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities [Internet]. 2022 Aug 22 [cited 2025 Sep 6];10(4):1997–2019. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9395863/

Ganguli‐Mitra A, Qureshi K, Curry GD, Meer N. Justice and the racial dimensions of health inequalities: A view from COVID‐19. Bioethics [Internet]. 2022 Mar [cited 2025 Sep 6];36(3):252–9. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9111442/

Hardeman RR, Murphy KA, J’Mag Karbeah, Kozhimannil KB. Naming Institutionalized Racism in the Public Health Literature: A Systematic Literature Review. Public Health Reports [Internet]. 2018 Apr 3 [cited 2025 Sep 6];133(3):240–9. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5958385/

Aaron DG, Stanford FC. Medicine, structural racism, and systems. Social Science & Medicine [Internet]. 2022 Feb 28 [cited 2025 Sep 6];298:114856–6. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9124607/

Roberts KM, Trejo AN. Provider, Heal Thy System: An Examination of Institutionally Racist Healthcare Regulatory Practices and Structures. Contemporary Family Therapy [Internet]. 2022 Jan 28 [cited 2025 Sep 6];44(1):4–15. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8794600/

Bump JB, Ifeyinwa Aniebo. Colonialism, malaria, and the decolonization of global health. PLOS Global Public Health [Internet]. 2022 Sep 6 [cited 2025 Aug 31];2(9):e0000936–6. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10021769/#sec004

Nassiri-Ansari T, Jose A, Syed K, Emma. The missing voices in global health storytelling. PLOS Global Public Health [Internet]. 2024 Jul 30 [cited 2025 Aug 31];4(7):e0003307–7. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11288427/